There are so many things about the Whitstable Biennale that are enormously attractive. The ethos of the organising team underpins every edition, and it is in part their intelligent art-led approach that makes it such a sincere and rewarding visitor experience.

The specific geography of Whitstable also plays a big role. It’s a compact, charming and historic Kent seaside town, with a hard-to-get-right character of unpolished chicness which forms the backdrop to the various presentations.

The title and theme of the biennale’s eighth edition is ‘The Faraway Nearby’, originally a quote from Georgia O’Keeffe and appropriated by Rebecca Solnit as the title of her 2013 book. This theme genuinely drives the content of the Whitstable Biennale: it is far more than marketing or window dressing, as can be the case in other biennials of art.

Director Sue Jones explains: “There is a lot on the news about refugees and Kent is the frontline, with growing numbers of unaccompanied children arriving. This was the background to our thinking. We didn’t want to ignore it, but we also didn’t want to be heavy handed.

“At the same time, I read Rebecca Solnit’s book, which is all about where home is, how you find a place that you belong. We thought that was a way of relating to the situation without stifling the work. We wanted to deal with political issues in a lyrical way.”

This is exactly what Sarah Wood’s beautifully scripted and precise documentary essay does. Shown on a relatively small monitor within the confines of a small vernacular beach hut, viewing Boat People is an intimate, thought-provoking and genuinely moving experience.

Wood’s script is enormously intelligent, capturing the complexity and heartbreak of individual situations, as well as our confused island response. She has managed to articulate a philosophical and historical overview of this moment of mass forced migration, relating it to a national character forged within our colonial past.

The artist seems to suggest that this is what has created our conflicting dialogue between “welcome” (a word repeated rhythmically throughout the film) and a kind of fallen nationalism manifesting as xenophobia. She won the Whitstable Biennale’s Open submission commission with this proposal, and it is well chosen.

With 15 new commissions in total, the Whitstable Biennale continues to support young and emerging artists to make new experimental and unusual works based around film, performance and sound.

The biennale includes a film programme curated by Gareth Evans (from Whitechapel Gallery) and a public programme which covers everything from themed walking tours, talks and a pub quiz to a creche. As in previous years, there’s also the Satellite programme.

While this makes for a dense programme, it’s a quieter affair than previously. There are tremendous subtleties in its new commissions and film programme, but fewer large-scale installations and in-your-face performances. For the opening weekend, Richard Layzell found a way to add delightful levity into his quirky performance that in a short period covered topics such as guerilla gardening, engineering, anthropomorphism and cruelty to cuddly toys.

In Fan Letters of Love, writer Alice Butler has created four ‘miniature chapbooks’ addressed to women writers she admires, including Kathy Acker. These tiny booklets with their deliberately home-made aesthetic contain text that is full of verve, excitement and character, functioning as both interpretation and homage.

“I’ve often thought of your writing as a sexy gift,” Butler writes to Acker, “the language moves, shakes and climaxes like an orgasm.” There are 175 copies of each distributed in four Whitstable shops for customers, art and book lovers to pick up and read with relish.

In a small and very dark beach hut, three visitors at a time listen to Trish Scott’s Medium, a playful and very funny 12-minute audio of recreated conversation.

For this work, the artist visited a number of psychics and asked them to predict and describe the work she would make for the Biennale. “I’m seeing something purple and furry,” says one, “simple but abstract”, says another. “It’s serious but not solemn,” says a voice. Indeed it is.

Also funny in the saucy seaside postcard tradition is the work and performance by Marcia Farquhar. A short film in the window of the Sundae Sundae shop depicts a Benny Hill-type incident with an ice-cream, recollected from Farquhar’s childhood. Andrew Kotting plays something more than a cameo part and ends with his trousers around his ankles.

Kotting also appears in his own right in two of his ‘Salons’, the first concentrating on how the notion of atmosphere might be experienced; and the second in which he presents work with artist and musician Conor Kelly.

Overall, this year’s programme is more moving image based than in previous editions, and some films would benefit from more rigorous editing. Without bombast or overblown hyperbole, Whitstable Biennial does a great service to the format and to artists, all within a relatively small budget. It’s a biennial unlike any others.

Whitstable Biennale 2016: The Faraway Nearby continues until 12 June. www.whitstablebiennale.com

Images:

1. Mikhail Karikis, Ain’t Got No Fear, 2016, video still

2. The iScreamers with Marcia Farquhar and others, Whitstable Biennale 2016. Photo: Bernard Mills

3. Sarah Wood, Boat People, 2016, film still

4. Alice Butler, Fan Letters of Love, installation view, Whitstable Biennale 2016. Photo: Bernard Mills

5. Trish Scott, Medium, 2016, video installation, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist

6. Marcia Farquhar, Based on a true story involving my mother, myself, an unknown old couple, a green ice cream and a hedge, installation view, Whitstable Biennale 2016. Photo: Bernard Mills

a-n bloggers Claire Manning, Matthew Kay and Emily Whitbread all have work featured in the Whitstable Satellite programme. Click on their names to read more.

More on a-n.co.uk:

A Q&A with… Alex Katz, painter

Baking, folk rituals and a grand procession: Tereza Buskova’s participatory project in Birmingham

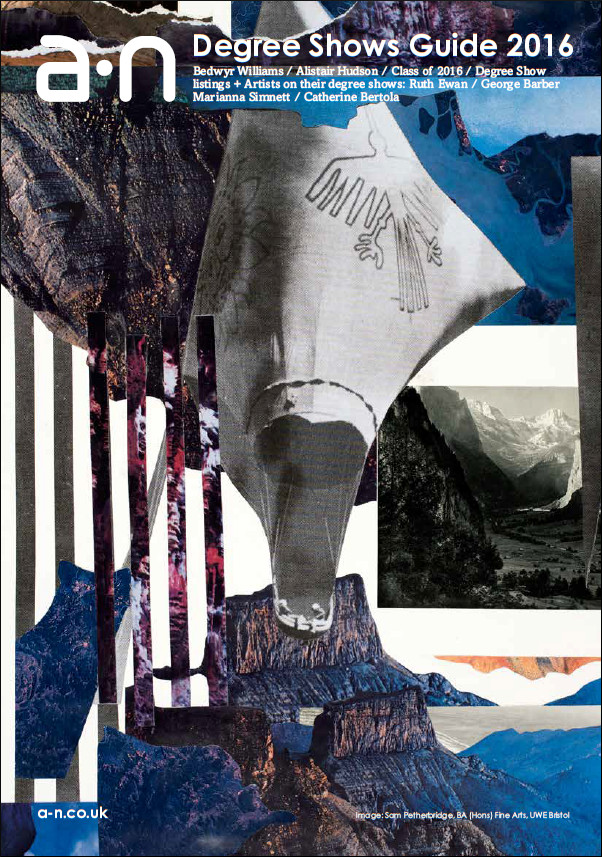

a-n Degree Shows Guide 2016