40 Years 40 Artists: Bobby Baker

Interview by Louisa Buck

Bobby Baker (born 1950 in Kent, lives and works in London) is an artist and activist, producing work that challenges preconceptions about domestic life and mental health across a range of disciplines and media, most notably performance. Over four decades her works have included dancing with meringue ladies, baking a life-size version of her family out of cake and making a series of diary drawings charting her experience of psychiatric treatments. Following an AHRC Creative Fellowship at Queen Mary University, London she was awarded an Honorary Doctorate in 2011.

Bobby Baker’s work Kitchen Show featured in the article ‘The gallery at home’ in Artists Newsletter, December 2000, p10-11, which considered the presentation of art in domestic spaces. She appeared in Artists Newsletter, November 1993, p32 in a feature about the National Review of Live Art, and in Artists Newsletter, December 1992, p9 in a report about ‘Fanny’s Big Ball’, at which Baker ‘gave a sample of her performance Cook Dems’. The event was organised by Fanny Adams, ‘an anonymous group of women artists,’ who had launched in 1992 to ‘bring the continuing sexism in British visual arts to the attention of a complacent art scene’. What did the 1990s mean to you both personally and professionally?

What did the 1990s mean to you both personally and professionally?

I would say the 1990s was absolutely the most productive, intense, crazy period of my career. And it was kind of wonderful. But it was also the period in which I cracked up, and now with hindsight I can look back on that time with a degree of insight and realise what was going on.

One of the things that underpinned it for me was that we had two children and my ex-husband Andrew and I were both in the creative industries and very affected by the financial crash in the late 1980s. We really struggled financially and nearly went bankrupt and though my work was massively booming in terms of bookings and growing notoriety I wasn’t very regularly or well paid.

I’d started to fall apart by the mid-1990s and I cracked up by 1997 – with all these different things going on, it was pretty hardcore. I got labeled as being disordered when in fact it was my life that was impossible. I see it as deeply misogynistic that the whole psychiatric profession labels anyone having a bad time as being a problem, rather than there being a problem in their lives.

How did your work develop in that time?

I’d say it’s just the way it’s progressing now. I do one show and then that leads to the next subject and very often working in a different form because it gets boring doing the same thing one after the other. The stress of that time actually made me hugely productive because the only way I could get the income coming in was by having new ideas and making new projects all the time. So I became a sort of machine for producing shows.

I had this great mission to make work about everyday life and women’s domestic lot, and I got such an incredible response to Drawing on a Mother’s Experience in 1988 that I came up with the idea for the Daily Life series. This was five shows over a ten year period which started with Kitchen Show and opening up my kitchen to the public in 1991. I came up with the idea that it had to be a domestic quintet, which was partly in response to the grandiose trilogies produced by male artists in that era.

So it began with Kitchen Show, then the second was How to Shop (1993), a spiritual journey in a supermarket in the form of lecture. The third in 1995 was a huge installation at the Southbank about women’s health, titled Take a Peek. The fourth, Grown Up School (1999), was about evil in a primary school and it took four years to get together because it was so difficult; and then when we finally got to Box Story (2001) it was just the best ever because it resolved the whole subject. That was a show about misfortune and how to survive it. Were there any key moments or turning points in this period?

Were there any key moments or turning points in this period?

I suppose I can’t speak specifically because there were so many small steps. What I would say is that it was very difficult to understand at the time what turning points were. It’s only when you look back on them and see how pivotal certain decisions were.

Kitchen Show in 1991 was the biggest step I’d ever made, apart from an edible family in a mobile home in 1976 when I made a life-size family out of cake in my prefab. I think the other shows were a strange sort of journey and I would say what I learned was so complicated and so gradual that when I look back on it, I couldn’t be brief about it.

But I think that what came out of it, and what’s behind every single thing, was trying to find the best way to communicate – to the widest audience possible – a set of ideas that was mostly extremely complicated about everyday life, that people could take in any way: at face value or they could see the intellectual side. It was about communication with people, so it had to not be in an art gallery. I wasn’t against art galleries, it’s just that the ideas wouldn’t have fitted in there and so they had to be in different settings, like shops and schools and whatever.

How did you become aware of a-n?

Looking back I was constantly guilty about a-n because I so wanted to subscribe to it and then I would subscribe to it, and then I’d fail to re-subscribe to it, and it’s that thing where you’ve got kids and a chaotic life and then you feel all guilty and ‘did I pay for it or didn’t I pay for it?’. Quite honestly in my 40s during the 1990s I was so intensely overworked and sleeping so little I was just never aware, so when I got a review in a magazine, I’d quite often missed it, I didn’t know, or it was a blur.

How significant was a-n in raising the issues of the time?

I knew it was a good thing, and I’d read it whenever I could, but it was always in this chaotic way. I longed to be more involved, I always felt very lonely because, although I was in the live art world, a lot of them came from theatre and I just couldn’t relate to it. They were great people, but they weren’t, in a way, my people. I really missed the visual arts. I missed people who understood where I came from and what the references in my work were, and I felt that a-n was that. And I felt almost outside it and quite desperate at times, because I didn’t know how to be part of it. And that’s gone on until quite recently, feeling on the edge and a bit clueless.

You’ve appeared in a number of a-n features and reviews, most notably in a live art feature that flagged up the 1992 show Cook Dems for ‘Fanny’s Big Ball’. Was that something significant for you or was that something that just happened to be popular?

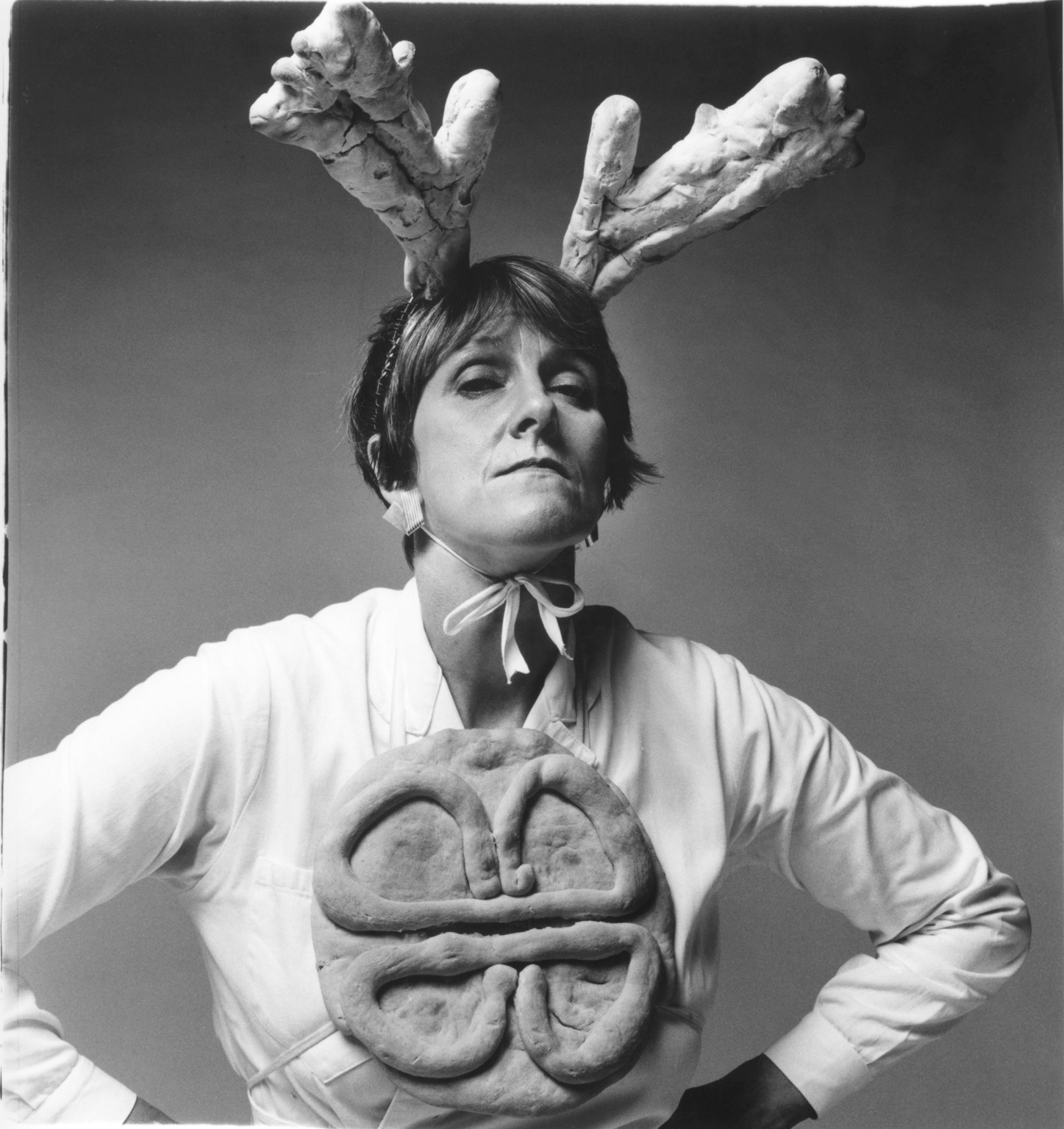

I remember I got the commission to do Cook Dems in 1990 from Glasgow City of Culture. It was a cookery demonstration to go anywhere. The idea was that I could pop up out of a cupboard wherever I was and demonstrate how to improve your status. So I made this outfit and I baked bread antlers to improve the status, breast pizzas to protect you against attack and insult, and a bread ball/board skirt to add glamour. We initially did it in the Strathclyde region in all these strange women’s centres and they just had no idea what was going to happen, then I’d ping out of this cupboard in this ridiculous kitchen and do a proper cookery demonstration, like Fanny Craddock. 30 years on what do you think are the key changes for artists starting out now?

30 years on what do you think are the key changes for artists starting out now?

During the 1990s the gallery scene changed, but it hadn’t really changed. Tate Modern wasn’t there and galleries were quite closed to those who went to them. What’s so exciting now is that we have these huge public spaces where people do go, they’re like modern temples where people see art – but it wasn’t like that in the 1990s. It was so elitist in some senses, you had to understand the language to see the work, and I think performance art in galleries is very often performance art for the cognoscenti. I’m interested in work which is just in a space, that people can happen upon, both of which they do now manage to do in Tate and it’s really exciting.

I also think now there’s a huge youth cult – to focus on young people can be an advantage but is rather piecemeal. I feel there’s quite a lot of pressure on young people but also a lot of support and excitement about their work. I suppose 30 years on there’s more visibility and pressure for people. But that also means there’s more opportunity. Ask me in another 30 years and I’ll be objective. It also seems much more competitive now but maybe it always was. When I was young there wasn’t any focus on you being young and emerging or anything, you just got on with it.

What advice would you give your younger self?

I would feel entitled to be an artist. Right at the core of it, I always knew I wanted to be an artist from when I was tiny, but I wouldn’t feel entitled. Does that make sense? I would just think ‘yeah, I can be an artist. I can be this and it doesn’t matter if I’m middle class or a woman or a mother. I am allowed and I am entitled’. That’s what I’d say. I’d be kind. I’d give myself more interesting support I suppose. I think seize everything but try to resist the pressure that you have to know what you’re doing.

Images:

Header: Bobby Baker, Cook Dems, 1990. Photo: Andrew Whittuck

1. Bobby Baker, Cook Dems, 1990. Photo: Andrew Whittuck

2. Bobby Baker, Displaying the Sunday Dinner, 1998. Photo: Andrew Whittuck

3. Bobby Baker, Drawing on a Mother’s Experience, 1988. Photo: Andrew Whittuck

Louisa Buck is a writer and broadcaster on contemporary art. She has been London Contemporary Art Correspondent for The Art Newspaper since 1997. She is a regular reviewer and commentator on BBC radio and TV. As an author she has written catalogue essays for institutions including Tate, Whitechapel Gallery, ICA London and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. In 2016, she authored The Going Public Report for Museums Sheffield. Her books include Moving Targets 2: A User’s Guide to British Art Now (2000), Market Matters: The Dynamics of the Contemporary Art Market (2004), Owning Art: The Contemporary Art Collector’s Handbook (2006), and Commissioning Contemporary Art: A Handbook for Curators, Collectors and Artists (2012). She was a Turner Prize judge in 2005.