One of the important aspects of Modernism, for me, has been the idea of the Western Tradition. As an undergraduate I took courses that covered the arts and literature, studying everything from Homer and the arts of ancient Greece to Virgil and later Dante, Chaucer, the Renaissance, and so on. For many of us, this great tradition was what Modernism is sitting at the end of, representing a crisis in how we see the world and ourselves. I’m put in mind of all this by the writer Malcolm Bradbury. I’m currently re-reading his novella/essay ‘Mensonge’, which explores in a satirical manner the loss of this tradition and the crisis Stucturalism and Deconstruction represent for it. I’m offering here a passage from the book, which begins by looking back at the Western Tradition and what it has meant. (Might not be so funny as a snippet):

‘Over that two thousand years, an entire lineage of philosophy, starting in the Eastern Mediterranean, spread westward and northward through then primeval forests by very bad routes, some of them still in use today, to bring home to people the notions of monotheism and conscience, deism and transcendentalism, the basis of western culture. The thought enlarged to incorporate evolutionism, materialism, scientism, psycologism, and then modern relativism, existentialism and Kierkegaardian fear-and-trembling. Yet it all had a common basis founded on the mind-body dichotomy, sometimes called the Cartesian cogito, though at other times not. Through it we learned, in a series of prodigious feats, how to dominate nature, build culture, master the organisation and structure of the universe, invent the collar stud and discover how to use the cellular telephone. We also learned how to write string quartets and make a fairly good soufflé, so perhaps it has not all been wasted.

But this tradition depended upon a stable concept of the self, and a reasonable firm notion of a reality out there, dense enough for us to be able at least to put a nail into it, and hang up a picture when required. It is nothing less than this whole tradition that Structuralism and Deconstruction are helping to bring to an end, opening up new and confusing opportunities. In this it has been the culmination of a process. Karl Marx demystified capitalist ideology, and showed how history worked, if we followed the instructions properly. Sigmund Freud undermined the rational ego, and showed us how the unconscious functioned…. Albert Einstein undermined traditional science showing that the world was a non-Euclidian four-dimensional space-time continuum…. Now Structuralism and Deconstruction have come along to complete the process, demythologising, demystifying and deconstructing our entire basis of thought, and suggesting other ways to use it. They have required us to redefine all our values and transform all our epistemologies, or at the very least to take a two-week holiday in the sun with someone we love very much and work out all future priorities very carefully. They have dismantled our preconceived framework of consciousness and perception, removed all our ideas of the transcendent and the everlasting, and dismantled the concept of the ‘subject’, or, as it used to be known in the old days, the person, so making table-setting for a dinner party very difficult indeed. They have done this by challenging our sense of essence and reality at its very root, in language……….In brief, Structuralism and Deconstruction are and remain important because they have quite simply disestablished the entire basis of human discourse’.

It is this sense of loss that sits behind a lot of Modernist art, I think, and, although it is not much discussed, it is one reason why abstraction developed – the loss of faith in what is ‘out there’ is balanced, in abstraction, by a focus on what our own engaged minds reveal as we go, disengaged from ‘things’. If Picasso’s multiple perspectives represented a loss of faith in how we see, then abstraction joins with science, geometry and abstract thought in the attempt to work out what might be there ‘behind’ the appearances that we can no longer believe in.

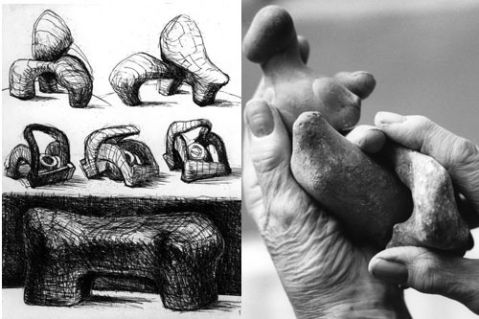

Attached: a piece that plays with some Cubist norms, with some constructivist leanings too. Yes – art that is unhappy about ‘out there’. Insular. Detached.