Those heavily fatigued days when tiredness suffuses my whole being, not only stop my limbs from functioning, but, and this is worse, make me feel as if my intelligence had sunk away. When I start improving a bit I have to dive deep to drag it back up again, for brief periods. In process now, but not out of the waters yet, and I’m rather uselessly railing against being in the state of un-. What I meant to do – write about The Beginning of History, which has taken on a complicated life in my head (and in a big bundle of notes, as well it should, it’s really quite an extra-ordinary show), has to be set aside for now, and I revisit, as I tend to when exhausted, old haunts. Only to find that this in many ways illuminates present pursuits.

Yesterday morning I was too tired to speak to a friend who’d rung me for more than a few minutes, frustrating for both of us. Today I sent her print-outs of my latest posts as if to remind her that I am not stupid, which I’m sure she never thought. I seem to, though, when I can’t command my body and brain into even small-scale action. In those moments my artwork, my writing here, are the proof

I need that I can still hack it. For similar reasons I crept to my computer earlier to look up my thesis, which was, amongst other things, about the memory of my cousin Edith (who ghosts in the pix above), the little girl in “Triumph of the Will”, and my relationship to both. I may have told you before: Edith was five years older than I and died when I was twelve. We only met a few times when I was small as our fathers had become estranged, but I found her again in an uneven pair of worn children’s shoes bought on a flea-market. They were of a different time (stuffed with a page of 1941 newsprint), but brought her back to mind with a bolt as they reminded me of the boots she wore, one of which had a high-raised sole.

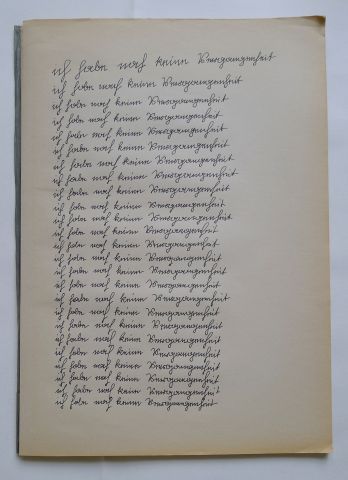

I was unable to more than scan the text with the help of edit/find (unexpected pun, I swear!), and my writing happens in fits and starts, but look at this:

“I can’t tell Edith’s story but can talk about my memory of her, which surprised me 25 years after her death, when last year I looked at the shoes that I had bought in Berlin some weeks before.” And then the sentence which made me catch my breath: “I imagine a photograph of Edith, which turns out to be of myself.”

I remember my surprise at the time, having searched old photographs at my parents’ house, to find that a photo I could clearly ‘see’ did not exist and instead featured me. It seems for a moment then I knew something about how memory works and fails, not just in theory. Something about the limits of imagining another’s life. I wrote in the end, mournfully: “Regarding Edith: I may be trying to bring something to do with her into a present, into my present, into another’s present, but never into hers.”

I want to write about the depth, the complexity of TBoH in a way that brings it to life for those who cannot see it (not many are finding their way to the gallery, alas) but haven’t quite been able to rise to the challenge. At the moment I feel more like a big fat spider, sitting in the web she’s spun and wrapping the prey caught in it in dense bundles of silk, beautiful in their own right but obliterating the shapes and singularities of what’s inside – only I do it with words. One thing I can say though, which I’ve come to understand through my post-outing engagement with the exhibition (I keep going on virtual walk-throughs): each work there, gloriously interesting in its own right, and skilfully, beautifully made, really becomes what it can be in the relationships formed/forming with the other pieces in this show.