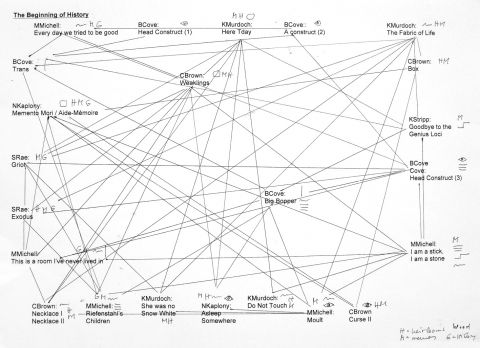

The Beginning of History – a view from inside

This exhibition stays alive in me, and every time I mentally step inside new layers of beauty and meaning beckon. Pain too, and challenge.

First thing you encounter is Ben Cove‘s Big Bopper – gorgeous, mysterious sentinel, with wool of many hues painstakingly wound around a tall, slightly curved plywood structure, on wheels. It looks sturdy and unstable, imposing and transitory. There’s a sense of impending motion (a ten-legged stagger) or unfolding (umbrella-like), although both are impossible. The wool stripes around its upper half seem pleasantly familiar, like those on deckchairs or a favourite sweater. The Big Bopper is unlike anything I’ve seen, so I’m clambering about for cues. I’ll have another look later.

For Nick Kaplony‘s Asleep Somewhere a pair of artificial eyelashes is projected on the wall in a rectangle of light, their perfect out-sized arcs childlike as well as theatrical. Going close you see how they are constructed, with cross-hatched webbing where the lashes are rooted. Little hovering smiles. The light a stage light on a star in a silent movie. A person is summoned, a memory; a dream of femininity and glamour. Desire drawn in failing light. Who’ll come across the threshold – a mother or a boy in drag? We will those eyes to open, look back at us, make us.

Right opposite a domestic scene is set, for a woman of a different generation, a different class, to put her face on with care and deliberation. Kate Murdoch‘s Here Today a summon too, through material things: a powder puff (even the word by-gone?) and make-up case placed on a bedside table painted in the same antique rose tone. A kind of stillness, suspension here, like in a room kept unchanged after a loved one died, only every time I come something has changed, as the artist unobtrusively intervenes, adds, arranges. The tone remains affectionate, tender; away from the lime-light, Kate’s nana is conjured in the daily effort of making herself beautiful. There’s a sense of warmth and respectability, of pride and aspiration. Skin English rose, with a hint of Scottish heather.

Now a half turn, drawn by the flicker of a film where a small rectangle has been cut out of an old head-board. Three people, a woman, a man, a woman, black, are ascending a staircase sidebyside, squashed together in an uncomfortable but mesmerising choreography, until they reach a bedroom where a drama quietly unfolds of complicated constellations, relations… Printed leaflets are fanned out on a small round table nearby, telling the story behind Shelley Rae‘s The Griot, of …, a slave, who married and was forcibly separated from his wife when sold on. How hard to write this, how easy. He married again and after the Civil War, now a free man, went with his new wife to find the wife he had to leave behind. They made a life together. A story you could see in a film and suspend belief, a story handed down in a family, domestic and public, where notions of race and gender are negotiated in pre-scribed prohibited spaces. A silent movie, until he/the man starts playing a mournful tune on a mouth organ, stretched out on the bed where earlier the women had lain, head next to toes, braced in a pledge of shared affections, but safe too in this world of three. No turning back now: pink skin is charged too, grandmothers firmly pulled into history.

Next to The Griot is Shelley‘s Exodus, a light box on which lie two pages of a letter, yellow with age, written in pencil in the 30s, here enlarged and printed. A letter written sister to sister by a great aunt of Shelley’s, descendants of The Griot, still struggling to make a life, a bare life, in circumstances still and ever reduced and restrained. That letter could be written today, the way things are going, with its worries about relatives out of work, a husband going astray, maybe homeless, and no New Deal in sight. The care of women is offered, of relatives, communities, inspite, against, with.

(more below —>)