So maybe the art is in the teaching?

The Chambers Dictionary defines the word “teach” as;- “To impart or give instruction as ones profession,

To impart knowledge or art to,

To impart the knowledge or art of” and “To exhibit so as to impress upon the mind”, amongst others. Yet its definition for “learn” reads;- “To gain knowledge, skill or ability in”. There appears to be a slight irregularity in these descriptions to me.

In response to my first post, David Minton questioned the notion of “skill” and proposed in it’s place “how can I best teach this child?”. I am so grateful for his input. It has raised issues I hadn’t considered and galvanised my thinking to such an extent that I’ve felt it necessary to change the name of this blog to The Art of Teaching.

The above explanations appear to reiterate David’s thoughts – there is no reference to “skill” or “ability” in the term “teach”. The primary term used is “knowledge” and this I suggest introduces a whole host of new and difficult calculations, particularly in terms of Art education. I propose that to teach art one must be a practicing artist to substantiate the above interpretations. One must have a relevant interest and erudition.

During the Renaissance an apprentice’s first tasks were humble: sweeping, running errands, preparing the wooden panels for painting, and grinding and mixing pigments. As the apprentice’s knowledge grew, he would begin to learn from his master: drawing sketches, copying paintings, casting sculptures, and assisting in the simpler aspects of creating art works, gradually attaining equality.

The best students would assist the master with important commissions, often painting background and minor figures while the Master painted the main subjects. Few apprentices could become masters themselves.

Once an artist did became a master, he could open his own workshop and hire apprentices of his own. Many workshops were versatile and could tackle many kinds of work: painting, sculpting, goldsmithing, architecture, and engineering. Artists were called to homes to paint portraits, decorate furniture, make silverware, paint banners, create sets for plays, make book covers or even design military machinery for war. In a brochure to patrons, Leonardo da Vinci listed thirty-six services that he could perform for his patrons. But artists were still a service business. Unlike today, artists did not create whatever they liked then put it up for sale. Art served specific functions.

The Renaissance was an important time for artists. They developed new techniques and expertise. Soon people began to admire their artistry as well as the subject of the artwork. By the late Renaissance, artists were no longer thought of as tradesmen. A master artist could become a highly respected member of the community.

This passing down of knowledge; the experience of making that is an essential element to learning, play a fundamental role, yet they lack some of the critical elements I propose that pupils require to learn effectively.

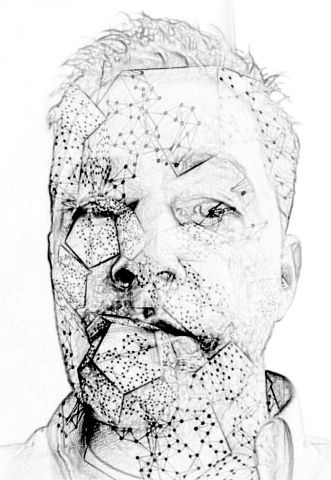

There are two components that I shall refer to in “The Art of Teaching”. Firstly, and for me most importantly, the Art teachers make as exemplars for lessons. Secondly, the key skills they deploy to initiate effective outcomes from pupils, that also stand as relevant pieces of contemporary art.