Mark Seltzer Serial Killers 1998

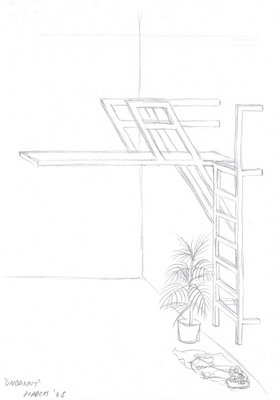

Mark Seltzer makes frequent reference to the uncanny in his 1998 book Serial Killers. Here are some excerpts:

There is something uncanny about how these killers are so much alike, living composites, how easily they blend in. The serial killer, as one prosecutor of these cases expressed it, is "abnormally normal": "just like you or me."

p.10

An embodiment of an uncanny spatial relation, the stranger's "strangeness means that he, who is also far, is actually near". … The stranger, if not (quite) yet the statistical person, begins to make visible the uncanny stranger-intimacy that defines the serial killer: the "deliberate stranger" or "the stranger beside me".

p.42

There is, in the experience of serial killing, a compulsive location of the scene of the crime in such homes away from home – hotel and motel spaces as murdering places. This is one indication of the radical redefinition of "the homelike" on the American scene: not exactly "no place like home," but rather only places "like" home. If stranger-killing is premised on a fundamental typicality, then the making of what came to be called, at the turn of the century, American "hotel-civilization" is premised on the mass replication of ideal-typical domestic spaces. It is premised, that is, on the uncanniness (unhomelikeness) of the domestic as such (an uncanniness perhaps inseperable from the psychic shocks of the machine culture of mass-reproducibility). Hence the repeated location of American serial violence in hotel and motel hells: the murder motel in Robert Bloch's novel Psycho, for example, or the even more lethal tourist hotel in his subsequent novel, American Gothic.

pp.47-8

What I mean to consider here are the relays progressively articulated between bodies and places such that the home, or, more exactly, the homelike, emerges again and again as the scene of the crime.

p.201

There is no doubt always something outmoded about the domestic and its constructed nostalgias – what might be called its uncanniness, if the notion of "the uncanny" (the unhomelike) itself had not by now become an all too homey way of naming that belatedness, its ambiguous causalities and periodizations (in effect, a way of endorsing a sort of better living through ambiguity). It is the vexed status of the homelike itself that I mean to define here. More exactly, it is the way in which the public spectacle or exhibition of "the private" in machine culture – museums or replicas of home as tourist site, for instance – seems to have become inseperable from the exhibition of bodily violence or atrocity that I mean to examine. These haunted homelike places – hotel and motel hells, for example – set in high relief the "gothic" rapport between persons and spaces, the distribution of degrees of aliveness across constructed spaces, the assimilation of the animate to the inanimate and mechanic.

p.202