Something like Kentridgemania has come to London. With the opening of a new show at the Marian Goodman Gallery in Soho, and his landmark theatre piece Ubu and the Truth Commission in collaboration with Handspring Puppet Company opening in mid-October, it’s going to be hard to escape his presence.

That’s not all. With drawings for Triumphs and Laments: A Project for the City of Rome – a forthcoming public art commission along a 550m length of the River Tiber in Rome – in the Italian Pavilion in Venice, as well work in the Istanbul Biennial, Kentridge is that rare entity: an enormously successful, critically acclaimed international art superstar.

The two major works in the Marian Goodman Gallery are the films Notes Towards a Model Opera and the show-stopping More Sweetly Play the Dance, a powerful eight-screen processionary danse macabre, with an evocative, ebullient and defiant brass-band soundtrack.

Kentridge is the child of Jewish liberal lawyers who defended victims of apartheid in South Africa, and moral and complex political questions underpin all his work. Notes Towards a Model Opera overtly references Mao’s Cultural Revolution, while More Sweetly Play the Dance connects absolutely with the human upheavals of political unrest, and more obliquely with Europe’s current refugee crisis.

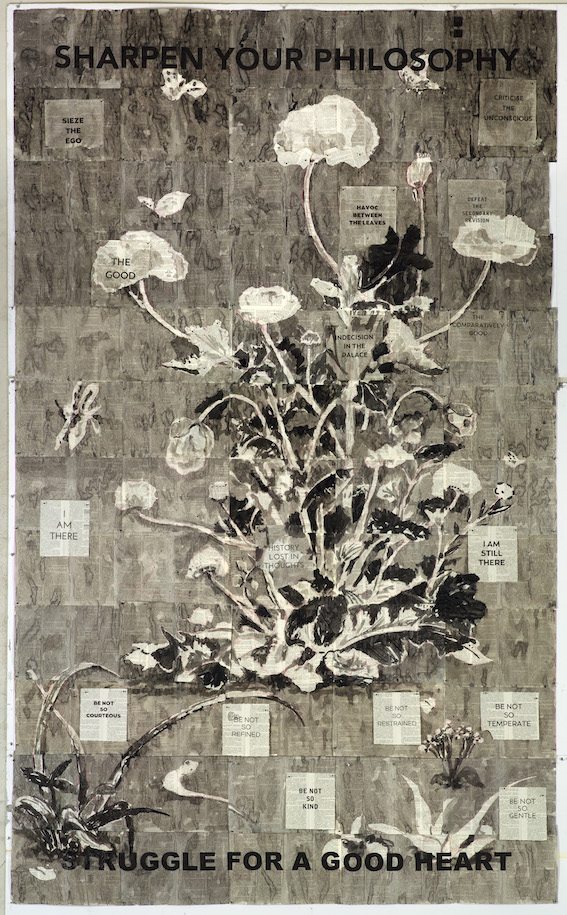

Often working on paper with charcoal and ink, Kentridge uses collage techniques on a large scale. The paper works often form the background of his films, as he animates the drawings and overlays this scene-setting with live-action moving image to create a highly distinctive aesthetic.

Erudite and intellectual, Kentridge talked the assembled press through his exhibition, explaining his influences and working processes.

What are the influences for these new works?

I took 1968 as my starting point. I was 13 years old, wishing I was five years older and living in Paris so I could be part of the student protests there. Students were ripping up the same paving stones that had been thrown in the 1871 Paris Commune, when the revolt had been based on Marxist ideas. At the same time, the Cultural Revolution was going on in China under Mao. The dancers waving red flags in Notes Towards a Model Opera reference the millions of Chinese students waving their Little Red Books, which easily translates into the socialist Red Flag. The background text and print refers to the large hand-drawn newspapers that students put up on the walls, and the slogans are adapted from those used in China in 1968. I’m very interested in these kinds of connections through geography and time.

What is the symbolic meaning behind your use of birds and cardboard cut-outs?

A prelude to the Cultural Revolution was the famine that preceded the Great Leap Forward. Mao hit on the idea of killing tree sparrows because they ate the crop seeds. Peasants were told to bang pots and pans to scare the birds and stop them from settling in trees, so that they would fall from the air, dead from exhaustion. Millions of birds were killed but of course the birds also ate the baby locusts, which were then able to survive and eat the crops, and that is what caused the famine. You can hear pots and pans featured on the soundtrack, but it also refers to more recent protests, for example, in Taksim Square in Istanbul, where people banged on their pots as part of their protest. The cardboard cut-out heads are like the way people carry images of saints, carrying their internal worlds with them. This is the kind of raw material that is brought into the video.

Tell us about your use of dancers in both videos?

They come from watching a lot of Chinese Model Operas, which were a kind of cultural expression of heroic propaganda. They were wonderful but absurd, sort of ‘how to defeat the Japanese army en pointe.’ There were also the images of ‘self criticism’, where people wore sandwich boards articulating their ideological failures. When I worked with the dancers I suggested we spend a morning looking at all these old model opera films and improvising.

In More Sweetly Play the Dance the idea is of a procession of people moving along and through the world. It takes the medieval form of the ‘long frieze’, led by the King, then the Pope, or religious leaders, aristocracy and so on. The medieval belief was that if you kept dancing, you could keep the plague and premature death away. So it’s superstitious but also defiant. It also has clear connections with the images we’ve seen recently of people walking towards an uncertain future.

The soundtrack is an integral and very powerful piece of this work. How did that come about?

We started listening to the music of the model operas and listening to African brass bands. In South Africa, brass bands are always associated with churches, and I found a piece of music that was exactly right and tracked down the band that played it. They recorded the music for me and they are also the people performing in the piece.

Can you say a bit about your working process?

My starting point is very much the form and the material. The cerebral process comes after making the objects when I judge whether something has come up to standard. Starting with an idea, or an overt ideology doesn’t work, although that doesn’t mean that messages don’t make their way into the works. I still make the drawings myself in the studio, using found texts. In the works in this exhibition, some of the pages are ancient Chinese manuscripts and some of them are from dictionaries. I use them for their associations rather than their literal meaning. But with the films the editing is always the major work. We filmed the dancers and the musicians many times and then layered them successively, putting them against the background landscape. The drawings get added at almost the last stage. You gather different paragraphs and arrange them into a story.

How does your work in opera inform your gallery work and vice versa?

I’m using similar techniques for Lulu, the opera I’m working on – fragmenting an image, projecting. They don’t feel like a fundamentally different activities; essentially it’s still standing over a table, working with charcoal and ink.

William Kentridge: More Sweetly Play the Dance, until 24 October 2015, Marian Goodman Gallery, London. www.mariangoodman.com

More on a-n.co.uk:

For more Q&As with artists, including Bridget Riley, Phil Collins, Rabab Ghazoul, Charles Avery and Marianna Simnett, use the Q&A tag