It started with sharing my own experiences of the depression I’ve sporadically suffered from for many years. What followed was a covert, harrowing and heartbreaking flood of private communications from many other artists, some of whom I know very well, most of whom I’ve never met.

They wrote of crippling episodes of mental illness from which they may have recovered, but which changed them forever; of being burned out, broken down, unable to cope; of lifelong struggles with intrusive compulsions or alien thoughts. Above all they expressed feelings of shame, fear and a need to hide their mental illness.

The initial article and responses to it led a-n to commission me to produce a series of new resources on mental health. In the process of doing this, it became clear that neither the visual arts nor our culture as a whole is ready for its own #MeToo or “I’m Spartacus” moment with regard to mental health – it’s still not an option for most people to call in sick or request reasonable adjustments at work because of a mental health problem.

I was however encouraged that there are small but undeniable steps forward, beyond the broadly positive buzz that open discussion of mental health issues is creating. Support and treatment are available once you know that you need it and can accept that help – which can be a huge leap to take.

London’s Bethlem Gallery has a small, artist-led team collaborating with current or past patients of NHS mental health services. Together they work very hard both to counter the general stigma of mental illness and to ensure that the artists are taken seriously.

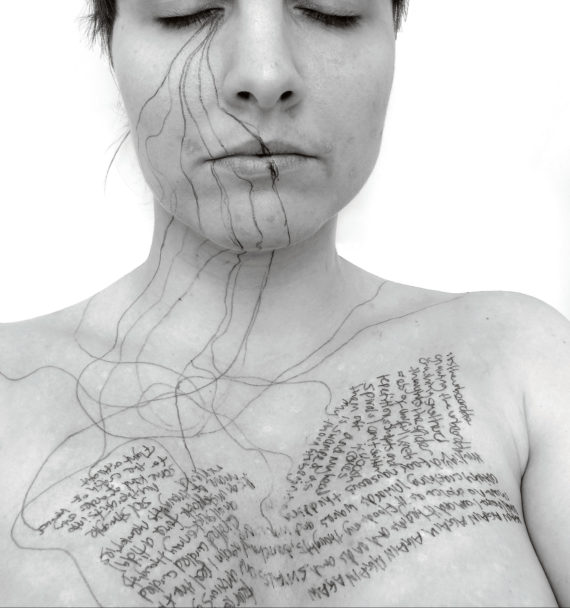

Liz Atkin has worked with Bethlem Gallery and made her lifelong struggles with body-focused repetitive behaviour a key part of her artistic practice; she is one of only two artists out of dozens I interviewed who wanted to put their name to the experiences they shared with me.

The underlying ethos of Niamh White and Tim A Shaw’s Hospital Rooms is also about respect, dignity and wellbeing, driven by a personal determination to effect change.

They bring highly accomplished and professional commissions by contemporary artists to secure mental health units, the main audience for which is an unapologetically small one of service users who would otherwise have treatment inside facilities that can at best be bland and clinical, at worst counterproductive. Shaw and White created Hospital Rooms after a friend was detained in a facility that White describes as “cold, clinical and not conducive to recovery”.

Looking back on my research – the things I was told, what I’ve written – I now have to wonder where the support is for all the people who work in the arts and are clearly struggling with mental health issues but aren’t doing so in a formal psychiatric environment.

It’s a fair objection that it’s tough to help people whose problems are not only largely invisible, but who also sometimes go to extraordinary lengths to hide their illness, if the stories of my interview subjects are anything to go by. The counter-proposition is that the visual arts sector, especially the big institutions and funders, just need to put their money where their mouths are.

Instead of merely talking about the importance of acknowledging mental health issues or diversity in press releases and among themselves at conferences, they could divert this energy and money into making the environments in which all artists and arts workers operate less stressful. They could start by paying them properly, accept that mental illnesses are real illnesses, and treat everyone who works in the arts with equal respect.

My correspondents never blamed their careers for making them mentally ill, but they unanimously confirmed to me what I already knew from personal experience: stress, burnout, low and insecure income, underpaid overwork, constant disrespect for the value of our labour and knowledge, and a general winner-takes-all arts culture make dealing with mental illnesses far harder. At the same time, it also creates a fear of admitting anything that might be held against us.

It’s no wonder people feel this way when some at senior or policy level in the arts breezily assert that artists burning out, breaking down, or dropping out of their vocations because it’s too stressful is par for the course and not a big deal (as documented by a-n and in my original article).

Meanwhile, leading academics, authors, art critics and popular culture generally all continue to romanticise, fetishise and monetise the mental illness, addiction, poverty and suffering of artists in the historical canon.

I now feel more strongly than ever that we need to talk about mental illness and mental wellness – all of us together, although some of our colleagues should listen more and talk less. By doing so, we can begin to make our jobs and vocations as powerful, productive and rewarding as they should be for ourselves and the people we make art for.

a-n members can access the Resources section at www.a-n.co.uk/resource.

Not yet an a-n member? Find out more about the benefits and join a-n today.

CORRECTION: this article was amended on 9 August to use the correct term in relation to Liz Atkins’ struggles with body-focused repetitive behaviour

Images:

1. Liz Atkin, Silent Lament, 2014. Exhibited in Liz Atkin, ‘Curdled’, at the ORTUS learning and events centre, London, commissioned by Bethlem Gallery as part of the Anxiety Arts Festival 2014

2. Mark Power and Jo Coles, project for the Relatives Room at Phoenix Unit, Springfield Hospital, South West London and St George’s Trust. Photo: Toni Hollowood; Courtesy: Hospital Rooms

3. Matthew Williams, Untitled. Courtesy: Bethlem Gallery

More on a-n.co.uk:

![A self-portrait by Vincent van Gogh with a bandaged ear. On display at The Courtauld Institute, London. Vincent van Gogh [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:VanGogh-self-portrait-with_bandaged_ear.jpg)](https://static.a-n.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/VanGogh-self-portrait-with_bandaged_ear-245x300.jpg)

Artists and mental health: depression is neither romantic nor inevitable

Artists remove works from Design Museum in protest at arms trade event

Independents Biennial 2018: giving artists what they want