When you’re depressed and your mind – the very thing you use to conceptualise and express yourself – feels as if it’s unravelling, it can be difficult to express what it’s like. Winston Churchill, the singer-songwriter Nick Drake, and my own grandfather all called it the black dog; always nipping at your ankles or sniffing along your trail. Churchill and my granddad brought the black dog to heel, living long and productive lives in their own very different ways. Drake couldn’t, and killed himself with his own antidepressant pills.

From my experience of the depression I’ve suffered with sporadically since I was a teenager, it’s a massive asteroid, Vantablack and absorbing 99% of the spectrum, screaming out of the void to crash into me in slow motion for the entirety of my conscious hours. Medication works well for some people but it never has for me, at least not without debilitating me in different but equally ghastly ways.

Thankfully, I’ve recently won the NHS postcode lottery and been referred to the excellent therapy and counselling that are still just barely clinging onto existence in my borough. Elsewhere, mental health support can be good, non-existent or appalling. Mental health issues – depression included – cross all boundaries of gender, class, culture and circumstance, and we shouldn’t automatically conflate depression with suicide. But, if I seem unduly focused on men, bear in mind that about three quarters of those who deliberately end their own lives are male.

Mental health and creativity

Mental health problems and creativity are popularly seen as having some kind of correlation. Sometimes it’s artists themselves cultivating the “mad, bad and dangerous to know” romanticism of their vocation. The art world and academia often give the impression it’s productive or even necessary for an artist to go crazy; the mental illness that contributed to the untimely deaths of artists like Mark Rothko or Vincent Van Gogh depicted as a prerequisite of their brilliance rather than an invisible, misunderstood and stigmatised disability.

Living with a mental illness or neurological condition doesn’t have the same romantic aura as dying because of one, nor does it elicit as much sympathy. In a recent article on a-n News for example, “at least two institutional directors commented that burn-out was perfectly normal and to be expected” among artists.

In other words, the pressures of trying to make their way in the current system contributes to thousands of people becoming unable to cope and, for their own preservation, withdrawing from careers whose current value to the UK economy is about £9 billion a year 1. Imagine the transformation if this talent was actively retained and supported instead of let go with a shrug.

With such a blasé attitude at the top it’s no wonder the arts are failing to make reasonable adjustments for people with mental health problems or lifelong conditions like autism, dyslexia and OCD. Employers are legally obliged to do so for people with physical disabilities, although in many cases they’re doing badly on that front too.

Depression and stress

Like many people, my depression can manifest with no clear instigator at all. It has also demonstrably been triggered by the stresses I face as an artist, which include (but are by no means limited to) insecure employment, money worries, constant rejection, and the apparent indifference or incompetence of people who may secretly be just as burnt out and depressed by their professional circumstances as I am.

It isn’t abnormal to be frustrated, angry, worried or sad about any of these common stressors. They happen to people in many jobs, regardless of their mental health. Nonetheless, I have no doubt that my resilience to depression has been whittled away by the massive pressure on artists to succeed and deliver consistently. This is often expected on ridiculously short deadlines and comically meagre resources, under circumstances in which nobody should be expected to function. Artists have to always be on, always available, always creative at a moment’s notice.

Our formal and informal networks also enforce the art world tyranny in which objections or noncompliance of any kind are seen as a reflection of the complainant’s flaws (‘failure’, ‘jealous’, ‘chip on the shoulder’…) rather than fair comment or cause for serious consideration. Artists never complain, the people they work for never explain.

When an artist can’t even object to blatant mistreatment and disrespect without the poisonous label “difficult” propagating through the grapevine, it’s tantamount to career suicide to publicly admit you’re struggling with your own mental health or you just can’t do things the way that most people do them.

Career suicide

But here I am, committing career suicide… again, oxymoronically. I have phases of every unanswered email being a deliberate stab in the heart from a villain of intergalactic stature, every encouragement and offer of help a bullying lie. And getting dressed to go outside can become an impossibility because people will see me, which is somehow the most horrifying thing I can imagine.

At other times I’m the person who probably has too many pictures of myself that I think are awesome – one of my favourite selfies is me as Van Gogh, after his self-portrait of himself with a bandaged ear. This was just after he’d cut off part of it and given it to a prostitute for reasons which are still unclear, but definitely weren’t rational.

The image isn’t meant to make light of his or anyone else’s struggles, nor to romanticise them. My intention is to celebrate his and my own artistic objectivity about a thing that is part of some people but isn’t really us. There are a lot of us, including many people who’ve learned to do a reasonably good job of hiding it.

I’ve never felt less creative or less productive than when I’m depressed. And even if they don’t think of themselves as ill or if their challenges inform their practice as an artist, I suspect there are few people who would say that being in the midst of dealing with anxiety or OCD or postnatal depression was conducive to their careers.

It’s neither romantic nor inevitable to suffer. It is, though, a terrible waste of talent, energy and diversity that the arts so desperately need.

1. Combined GVA (gross value added) of museums, galleries, libraries, music, performing and visual arts in the UK, 2015

Images:

1. A self-portrait by Vincent van Gogh with a bandaged ear. On display at The Courtauld Institute, London. Vincent van Gogh [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:VanGogh-self-portrait-with_bandaged_ear.jpg)

2. Artist and writer Alistair Gentry as Vincent Van Gogh. Courtesy: the artist

More on a-n.co.uk:

In Brief: 14-18 Now announces nationwide cultural programme for culmination of WWI centenary

Procreative space: new studios for mother artists and children open in London

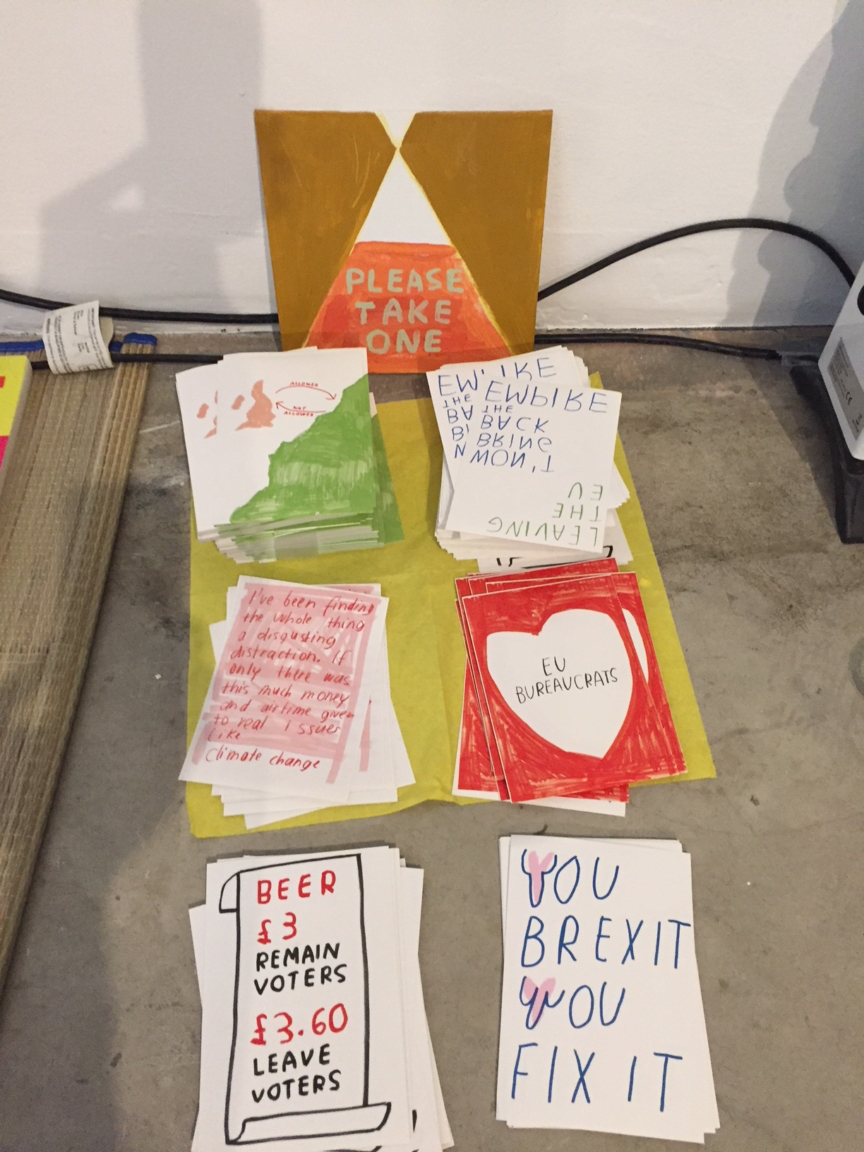

Organise With Others: a post-referendum ‘reactivation day’ for artists and the arts