Clare Woods’ painting practice has in recent years moved away from the slick gloss and enamel abstract landscapes for which she has become best known.

Turning her attention to oils on aluminium, some of the Herefordshire-based artist’s most recent work has instead taken a turn toward more figurative, large-scale work that takes its starting points from a wide range of found photographic images.

The results, as seen in last summer’s ‘Victim of Geography’ at Dundee Contemporary Arts and in her current solo exhibition ‘Reality Dimmed’ at Warwick Arts Centre’s Mead Gallery, are seductive and disconcerting paintings that express a huge variety of emotional subtleties.

Originally trained as a sculptor, Woods describes her paintings as “almost object-like” and they are painted flat on the floor of her studio. In her works, the textures of skin and cloth, in particular, are rendered almost sculpturally via her deft handling of material.

Woods’ paintings are held in numerous art collections including the Albright-Knox Gallery in Buffalo, USA and the Arts Council England Collection. Her piece, Carpenters Curve, was created as a permanent public work for the London 2012 Olympic Park.

‘Reality Dimmed’ is comprised of eight large paintings hung in one space, the majority of which measure 3x2m. How do you arrive at decisions about scale?

I really like working big but you can’t work on that scale just generally in your studio. I did a show at Dundee Contemporary Arts in the summer which is a similar scale museum to the Mead. To be given that space to make a show is the perfect opportunity to scale up the paintings.

Can you tell me more about the processes of working at this size?

The paintings are made on aluminium and I work flat so they become like tables. It’s a strange thing because they are so huge I can barely reach the middle but there is a very physical relationship with the process. Five works in ‘Reality Dimmed’ were made for the Mead and three came from the Dundee show. When I do a show, I’m not just thinking about the walls but the void of the space and the relation of works in there.

You’ve noted that the process of painting has become much faster for you. How do you achieve this at this scale?

The thinking and the development of the image are much more separate to the painting. When it comes to the painting, I am just painting. It’s still an eight, nine-hour job but it’s much more challenging. I used to mask off areas so I could paint sections whereas now I am painting in one go: it has to be painted in one go. The execution of paint on panel became much quicker while I was working on the Dundee and Mead shows. It’s a process of me engaging with the paint and the surface and that’s all that’s really happening at that point.

How much of a perspective of the painting do you have during its making?

None. I don’t look at them until I stand them up and that’s when I know if they’ve worked or not. Rarely do I work back into them. Most of the pieces in ‘Reality Dimmed’ were complete when they were finished.

It seems like quite an instinctive development process …

Mostly source images find me or I find them when I’m not expecting to. I take my own images as well, though nothing is ever set up. I don’t set out exploring or looking for something. There is an editing process but although the execution is broken down into photography, drawing, painting, the whole practice isn’t that planned. When I finish a show I almost can’t imagine what the next painting will be but it happens.

The exhibition text talks about health and sickness and you mention images of major events such as 9/11 being of significance. How and why do you select these?

The image has to affect me. When I’m working with the image, I’m tweaking it a little bit and deciding how it relates to me or affects me, conceptually or emotionally. I have to think about how I can execute it in paint to become almost object-like. This is also instinctive and I don’t only use this type of imagery. In the painting Reality Dimmed [all works 2017 unless otherwise stated], there are two pillows propped up, and an empty bed in My Horrible Head, so they are not all about trauma but found images that do something to me. I’ve spent years trying to figure out how images relate to each other but it was only last summer that I realised they don’t relate to each other, only to me in some way. The works are about being human, about being alive – they don’t have to be over thought.

The exhibition is quite pared back, with just eight large paintings and a smaller one, Lost Leap (2010) in the gallery’s education space. Did you choose from a wider selection or did you make eight?

There are others but these work together, were painted together and demand a lot of space.

Can you say more about the titles? You’ve mentioned collecting these in a manner similar to photographic images.

Exactly. I find these in street names, on the radio or a group of words will stick out from a book. I’ve probably got about 30,000 titles on a list. When the work is finished and it is stood up and complete, I kind of know what it’s going to be called. Titles are really important to providing a non-visual way in.

Looking at the titles of the Mead paintings, there is a violence but also an almost literary overtone. They could be titles of an Agatha Christie novel, for instance, which adds a playful or near-comic angle.

I like that idea. I hadn’t really thought of it like that – like book or chapter titles. I’m never really thinking about what the other titles are – they are unique to that painting. I think I’ll be looking back at some of the other show collections to see what they all sound like together.

The Dementor has probably the most obvious literally reference via the Harry Potter stories.

I hadn’t thought of that either. It’s what I call my son because he drives me crazy and [the painting] is based on a photograph of him. The work says something about a fear of people. Karen Lang, in the exhibition catalogue, speaks about that painting really well. She just gets it.

The Mead Gallery owns your painting Lost Leap. Was this the start of the conversation with them?

Yes, and then the Mead’s curator, Sarah Shalgosky, commissioned me to make a work for The Hive in Worcester so I worked very closely with her for a couple of years. She became someone I spoke to a lot about the work. It’s fantastic to be showing in the ‘old’ Mead as it’s going to be redeveloped soon but has a really strong history of showing contemporary painting. The great thing about being an artist is that you tend to hold on to a couple of people along the way that are really nourishing personally and for the practice.

You are showing in various other exhibitions too.

At the Towner Art Gallery [in the exhibition ‘A Green and Pleasant Land’] is an older piece called Daddy Witch (2008) and I’m showing collage pieces at Alan Cristea [in the group show ‘History in the Making’]. In February I have a solo show at Simon Lee’s Hong Kong space called ‘Rehumanised’, of new paintings made alongside those of the Mead show. These are much smaller though, with the largest being 2m square. Short Bad Day, from the Mead catalogue, will be showing there, with others down to 15cm square but similar in terms of content to those in ‘Reality Dimmed’. I wanted to go a bit more intimate after a run of large paintings, though this is proving to be a bit of a challenge. It’s really hard to make a small painting! I also have a show in Copenhagen opening in September, so that will be the next big focus.

‘Reality Dimmed’ is at the Mead Gallery, Warwick Arts Centre, Coventry until 10 March 2018.

www.warwickartscentre.co.uk/whats-on/2018/clare-woods

Images:

1. Clare Woods, Something Bigger, 2017, Oil on aluminium, 300 x 200 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Simon Lee Gallery London / Hong Kong

2. Clare Woods in her studio. Courtesy: the artist

3. Clare Woods, The Last Word, 2017, Oil on aluminium, 300 x 200 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Simon Lee Gallery London / Hong Kong

4. Clare Woods, The Dementor, 2017, Oil on aluminium, 300 x 200 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Simon Lee Gallery London / Hong Kong

5. Clare Woods, English Murder, 2017, Oil on aluminium, 300 x 200 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Simon Lee Gallery London / Hong Kong

More on a-n.co.uk:

Scene Report: Coventry – seizing new opportunities for the visual arts

Arts calendar 2018: exhibitions, conferences and other events

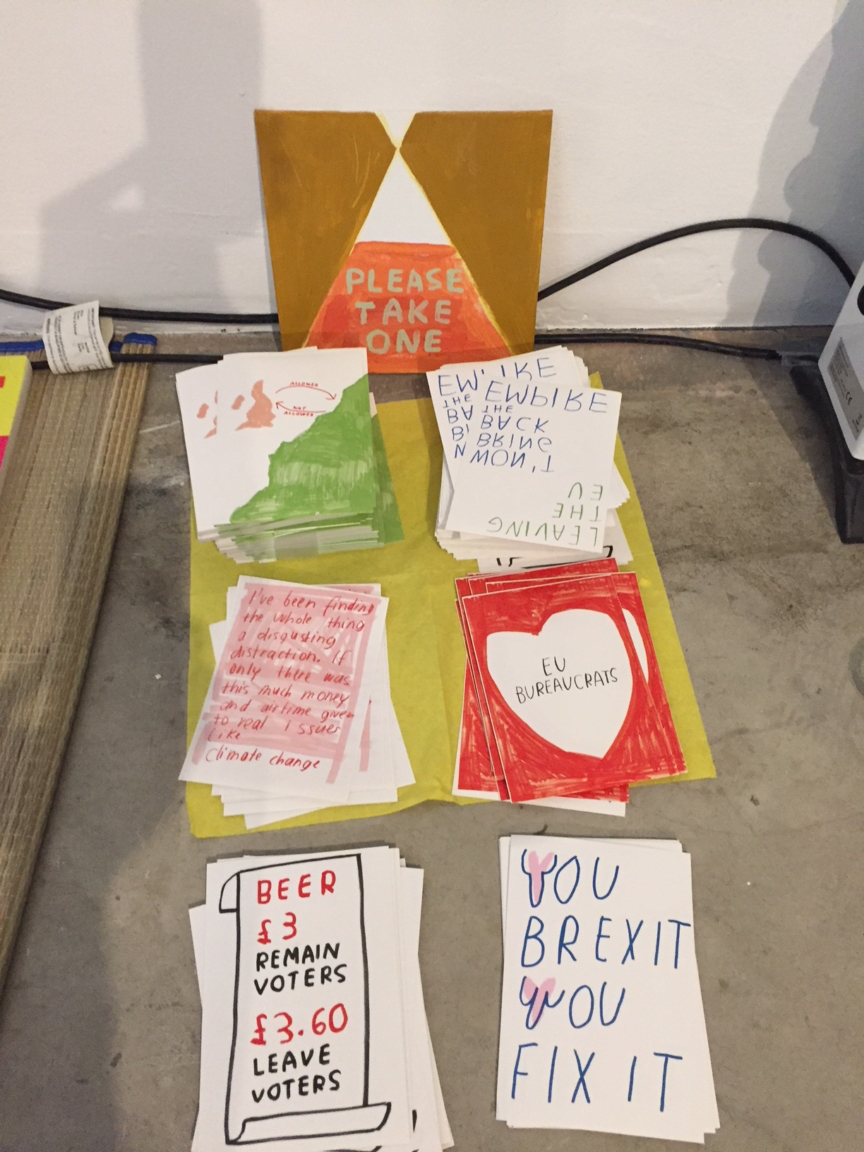

Organise With Others: a post-referendum ‘reactivation day’ for artists and the arts