- Venue

- Collyer Bristow Gallery - currently closed 4 Bedford Row London WC1R 4TF

- Location

- London

‘Me, Myself and I’ is an exhibition investigating artists’ self-enquiry and expressions of the interior self. Works speak to a range of lived experiences recalling personal and political struggles, family relationships and memories of childhood. Across painting, drawing, photography and assemblage the show reflects on themes of freedom and solitude, collectivity and belonging, disenfranchisement and loss. In liminal spaces between fact and fiction, the fantastical and the everyday, twenty artists grapple with – and celebrate – the complexities of identity, selfhood and finding one’s place in the world.’

Curated by Rosalind Davis, at Collyer Bristow, Lockdown arrived before I was able to see the show. Working from a computer has been instructive in itself. The ability to get close breaks down. Enlargement after a certain point degrades what is visible.

A sense of scale is elusive. Ultimately, haptic systems will create seamless experience between the ‘real’ world and digital reality. Some of these works have proven more difficult than others to ‘see’, but then there is only the computer screen’s word for it. The Digital image ‘textualises’ the real experience of real presence into one of reading.

In a Cat’s Cradle of an exhibition, strands of self and identity crisscross, a procession of viewings and re-viewings. No walking to be done, images linked and cross-referenced, dimensions scrutinised, artists researched, notes made, all from a chair, birds singing in the background. And the doorbell will be heard, the parcel received, groceries delivered.

Ken Kiff’s “Man With Paraffin Stove” 1965 sits nameless, head turned quizzically around with a look that seems a little uninviting, as though interrupted in the execution of some secret act. ‘Who are you looking at?’ At his feet a pair of scissors. In his hands a portrait, a potential victim of scissoring? Further into the painting, the Paraffin stove is a cool green against hot yellow. Kiff’s brushing will’s the paint to speak, ‘Do you know what I mean?’ Conversational uncertainty pervades the image.

Ten years later in ‘Unlikely Angel’,1975, uncertainty becomes anxious, introspective. Both artist and model avoid our gaze and each other’s. There is yearning in urgently scraped surfaces and rich, muted, melancholy colour.

The titles of Charmaine Watkiss’ large drawings attest to unanticipated, consequences. ‘They Didn’t Come to Stay’; the stern expressions of Three assertive West Indian Graces express a mixture of anger, disappointment, puzzlement.

A woman announces ‘We Are Here’, as she creates a metaphoric cat’s cradle of interconnections that can fall apart at the flick of a Home Office finger.

There is the ethnic look of a museum piece in Marion Michell’s ‘Sometimes I Think That When I’m Sleeping I Must Most Perfectly Resemble Them’. Its baby-grow beginnings, inverse – ziggurat, edge upward to arms spreadeagled by a batten against a wall. ‘You have to be cruel to be kind…’ in the caring business of forming the growing child’s child. Helplessness and panic induced by such pinning will clothe a lifetime. The title resonates. In sleep is temporary release; arms can embrace, apprehensions and tensions subside, dreams can be true.

Kate Murdoch’s installation ‘Objectification 2020’ is similarly evocative.

A pretty pink girls’ dress, a reproduction of a painting, a kitsch doe-eyed girlchild holding a kitten, a doll, ornaments, makeup, tutu, mirrors and bedroom furniture, a well-used ironing board, its scratched ageing a sign to the doe-eyed girl-child, pastry cutters, implements of domesticity, things, owned things, loved things, full of hope, Mine, Hers, Yours, Ours, Us. A group of porcelain ornaments, idealised, romantic figures of young girls, their mouths taped into silence, stare into a mirror. Girls should be seen and not heard. A velvet covered stool, something posh about velvet, evocative of better-off relations who lived by the sea, and aunts who seemed respectable. Possession and ownership marks Me and Mine, things and minds. They offer protection from grubby truths resident in bodies and minds which must be kept distanced, remain apart, lest through mutual infection an immunity should develop, to life-stifling conventions of the herd.

The demeanour of Linnett Panashe Rubaya’s young girl echoes the uncertain title of her painting, ‘Untitled 8’. She looks out sideways beyond its confines, seemingly reluctant to remain, reluctant to leave, its edges a constraining force, composition as oppression.

Will Harman’s desire for humour and fun in his work is infused with edginess. A meeting between the ‘Jenkin’ of Georgina Clapham’s painting and the various characters on the pathway of Will Harman’s ‘Trellis’ might be instructive. A siren-call of self parody rattles around a gathering of fag-ends and its dog in our winds of Brexit’s change, as contrary prejudices and preconceptions fight for the high ground.

And imagine in a moment of Jekyll and Hyde reversal Jenkin is painted with Harman’s ‘painterly crudeness’ and the characters of ‘The Trellis with Georgina Clapham’s mimetic attention… What then of selves thus depicted? In such a cross-dressing the other presents as oneself with all the discomfort that sudden revelation might induce. Like walking a mile in another’s shoes, living a minute in another’s style has cathartic potential.

Developed from photographs, Sikelela Owen’s work is of an altogether gentler disposition. – Washes coalesce through degrees of opacity, distilling painted presence from photographic detail in a gently gestured, generalised sense, of a particular child. Image softens into memory, stretching back for that decisive moment, that point in time, that day, a desiring, poignant softening.

Everyday experience features in the work of Aya Haidars, her piece, “Wish You Were Here’ is very much in the present, washing and the present hanging out to dry. ’Trimmed kids toenails’, ‘produced milk’, ‘pumped’ ,’dried dishes’ are some of the terms embroidered on items of clothing .’Scrubbed poo off pants’, points to uncomfortable domesticity. ’Wish you were here’ seems less an expression of desire than a cry for practical help to absent selves. Poo, fingernails, milk, pants, dishes, details that loom large in lives, form a continuum with Kate Murdoch’s installation.

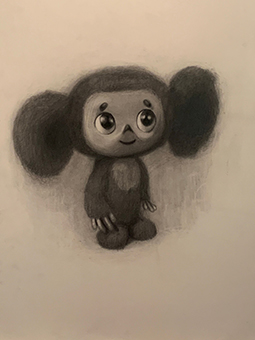

‘Cheburashka’ and ‘Bu-Ra-Ti-No!’ are drawn from their original creation by Eduard Vispensky and Alexei Tolstoy, by Margarita Gluzberg. ‘Cheburashka’, a small, bearcub-like, large eared creature ‘unknown to science’ has been transported from his home having fallen asleep in an orange crate. Unintentionally migrant, endearingly innocent with nowhere to stay, he is refused a place in a zoo because he cannot be classified; the zookeeper does not know what he is, so cannot allocate a cage. He suggests a telephone booth. Rejection might weary his yearning to belong but his innocence remains pure.

In a telling re-formation, hyphenated and exclaimed, Gluzberg embeds Buratino’s knowing naughtiness in his name. ’Bu-Ra-Ti-No!’, makes of the name a sharply audible thing, a rebuke that resonates in childhood memories.

By contrast, Wendy Saunders pieces are almost featureless in terms of particular identities. Not minimal, a minimum, not descriptive, representative, their connection with the everyday head a determinedly tentative thing. What you see is what you see, as it were, but….. as with ‘real’ selves, getting to know them is both an immediate and a subjective business, considered reflection following ‘gut reaction’.

The notion of neurodiversity is particularly relevant to questions concerning the ethics of selfhood, democracy, diversity and hegemony, and apt here. In ‘What We Are most Afraid of Has Already Happened’ neurodiverse artist Laura Hudson plays spatially with existential threat. Hyphen-pains seem to flow from the heart of of what might be a female figure in a Space or diver’s helmet. On her arm, an inflatable armband. Sink or swim or both? Either way is a struggle. And for good measure, a pair of antennae sprout insect like from the helmet. Human or other?Spatial ambiguity created by the coincidental junction of the bottoms of her jeans with the border of a green surface, whilst blue paint truncates her body and renders her hand non-existent, constitutes an existential threat.

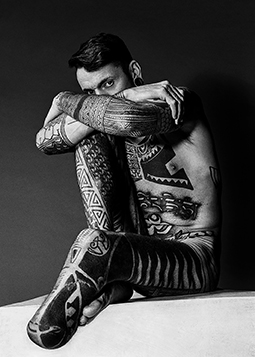

The eyes have it. In Manon Ouimet’s ‘Portrait of Andrew’, elaborately tattooed he binds into himself, eyes probing our response over the top of tight gripping arms, his amputated leg beautifully drawn by the photographic process. To find elegance in this shape, in this leg, in this part-leg, in this print, this print’s distanced elegance, valorised as ‘Giclée, seems, at first, shaming.

We look over Paul Benjamin’s shoulder, “The pieces Paul created when he was diagnosed with terminal cancer chart his reaction to his illness, providing him with a way to process his prognosis. They became a record of his journey, documenting positive and negative experiences…’ Jaqui Benjamins from Press release Me Myself and I . And from the artist, ‘….lots going on no time to mess around or waste…’ sprayed red, washed grey . ‘Hospice’, mid-sentence, written in ink, bleeds into washed grey, struggles to make itself readable as little rivulets of wash trace the passing of time from nipples of paint to the bottom of the page.

Boughton and Birnie, two selves very busy, a meta-self concatenation of things, events, paint and marks, scuffs and scumbles a lime, blackcurrant, orange cocktail…………in images garnered from the internet, colouring fruit-sharp, flavoured, yellows and violets, acid oranges to make the mouth water, but with contrary browns, earthy greens, evoking feelings from childhood as a sweet falls to the ground to be contaminated by dust.

A Pierrot automaton holds his head high as if in a state of ecstasy in ‘Wall’ Marie Harnett’s small pencil drawing. Light and pencil round and soften the smooth look of silk. A pattern of light as though through a blind is picked out in the far corner, the kind of light that I remember spilling onto my bedroom wall early on a sunny morning as a passing milkman’s bottles rattle in the cool air. A girl in a silk dress, an angry boy, fists closed in a fit of rage, strange butterflies, a sense of familiarity and uncertainty create a softly disturbing hypnopompic image based upon still frames from ‘Crimson Peak’ a Gothic romance directed by Guillermo del Toro. In a final resonant speech the heroine of the film, Edith, speaks to us….‘Ghosts are real, There are things that tie them tighter to a place, very much like they do us. Some remain tethered to a patch of land, a time, a date, a spilling blood, a terrible crime. There are others of them that hold on to emotion, that drive loss, revenge, or love. These never go away.’

The 2008 film ‘I’m Not There’ explores the notion of a multifaceted self, points to the idiosyncratic, in six aspects of Bob Dylan.The title of Erica Winstone’s ‘I’m Not There’, becomes mantra-like, three insistent words, a present denial of presence, the self as a subterranean homesick flow of mainstream, eddies, backwaters, currents, flotsam and jetsam of identity rising. And sinking.

In the scene in ‘Creek’, Eleanor Moreton’s landscape rendered with urgent, sketchy brushing, sits a man in red trousers; a woman floats like Ophelia below. Sharon Tate? This presence of one who might be Charles Manson is there for all the world like any of us might be, idling away the day.

‘It’s Going Darnall’. Conor Rogers’ two old boys place their bets in a shop in Sheffield. The title’s ironic humour makes light of uncomfortable truth, its affectionate undertone reference to an economically deprived housing estate. A triptych painted on betting slips, it makes real a short path from hope to disillusion as race and bet are lost. Cheap printed paper signals transience, slow decay. The business of painting on such stuff, of placing art on the artless, an act of both caring and desperation; two old boys, betting slips in a meritocracy; no Giclée here.

The first act of self is to receive the name around which identity accrues, and the struggle-puzzle of form and content begins to surface. This exhibition, its multiplicity of form and its contents, is evidenced by the shaping of its works. The act of making, shaping, is a bodily thing. Compare Will Harman’s ‘Painterly crudeness’, with Nathan Eastwood’s painterly softness, with Ken Kiff’s earnestly cared-for brushing; the act is the thought, ‘self’ generated, through material, technique, medium. Content is content is content. Medium reveals the flow of living, and how to live, is the sum of its possibilities, analogous to self, and ‘Self’ the medium in which the ‘I’ is drawn. Notions of style and taste, conventionally misrecognised as superficialities, go to the heart of the matter. The self is a fractal, autonomic thing.

https://collyerbristow.com/gallery/

1 ‘Neurodiversity is a concept where neurological differences are to be recognized and respected as any other human variation. These differences can include those labeled with Dyspraxia, Dyslexia, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Dyscalculia, Autistic Spectrum, Tourette Syndrome, and others’