- Venue

- FACT and Tate Liverpool

- Location

- North West England

playing with light and time

This retrospective of the work of Nam June Paik (1932-2006), sometimes called the pioneer of media art or the father of video art – though these terms don’t begin to describe him – in the most important exhibition in Great Britain right now, and I believe it will be, in the end, the most significant exhibition of 2011. That it’s being held in Liverpool might surprise some London-centric types, but of course the Northwest has long and deep roots in the video/new media art sector: for example the various Video Positive exhibitions and the founding of the excellent FACT (Foundation for Art and Creative Technology) centre, among others.

The retrospective is spread over two centres, FACT and Tate Liverpool, allowing the breadth and depth of Paik’s achievement to be fully experienced. The separation also allows the viewer to have two entirely different experiences. Yet in its curation, there is unity and clarity of vision in the way the work is presented. Because the show is so rich, I saw it over two days. The Tate presents a historical introduction to Paik, as well as presenting some of his most significant works. FACT presents a huge (and comfortable!) video lounge where a broad range of longer Paik works can be selected and screened.

So, what about Paik, then? Who was he, and why do we want to see a retrospective of his work? Academic and intellectual, avant-garde artist, performer and director of television programmes, visual artist and musician. How to get a handle on Paik? Like most people interested in moving-image and electronic art, I’d heard of Paik and seen some of his work in other exhibitions, but it always seemed a bit hazy to get an idea of exactly what he did, why he did it and how. This exhibition expands on all that, in a way that is both enriching and inspiring.

When I started writing this, I ended up with a massive mind-map, and a realisation that this review was in danger of being an MA thesis. And all I want to do really is to get you on that train to Liverpool, to see it for yourselves. So, I’ll give you a run down of what I found significant, with the promise that you will find something there significant and fascinating that is specific to you.

Paik’s work is rooted in the artistic tendency which we see appear in the actions of the Dadaists and the early Surrealists, without actually being connected directly to them. Paik was a Japanese-educated Korean, who moved to Germany to pursue his studies. The Korean War had uprooted his family home and he had both the opportunity and necessity to make his own destiny, and he chose the avant-garde. Initially working with experimental music, leading to collaborating with John Cage (Tate) , Paik’s innate curiosity and sense of fun led him to consider the medium of television and video as ripe for encounter.

As well as his active participation in Fluxus “happenings” and other de-materialised art actions in the US and Germany (Tate), Paik leaned toward a Dada aesthetic, seen clearly in the costumes he designed for and with his collaborator Charlotte Moorman, such as the TV Bra (Tate). The spirit of the Cabaret Voltaire and Hugo Ball’s home-made costumes and performance is here. This same critical yet playful spirit can also be seen in the live satellite transmissions he made for US public television (FACT).

I’m using the Dada reference deliberately, because one thing not often discussed about the Dada is that they were a group of antiwar refugees and deserters. Paik was also a refugee of a kind: from 1950 to 1953 Korea was riven by civil war and after that, the country was divided, as it remains today. Although Paik wasn’t personally involved in the situation, the Cold War was a reality to him, and this clearly fuelled his constant striving to understand and work with the idea of communication. As it developed much of his work becomes concerned with breaking down the borders between east and west. He did this with his synchronised live satellite transmissions (FACT), which were televised, and also in one of his most poetic and affecting moving-image works. This is Guadalcanal Requiem (FACT), with Paik and Moorman on the Pacific island where one of the worst US-Japanese battles of WW2 was fought. A kind of anti-television documentary, this work is stunning, expressionistic and richly layered. (Interestingly, Bill Viola was one of the camera operators on this project). It is surrealistic and political, as Paik asserts that actually, global conflict is the product of cultural miscommunication. It’s a pity really, that this work, and work inspired by this, are not on our TV screens of an evening.

One aspect of Paik’s work I hadn’t been very aware of before was his exploration of spirituality, in particular the spiritual nexus where nature meets technology. This is shown most wonderfully in a series of small installations in the Tate. Each work has a TV monitor, some working and some hollowed-out, and a small Buddha statue. The Buddhas impassively watch the screens: some watch themselves, some watch a candle burning down, some watch nothing at all. They contemplate, endlessly. Buddha sees everything: nature, the self, the world. (One of the installations substitutes Rodin’s Thinker for the Buddha, a nod to the Western tradition which Paik also encompasses.) But Paik does not use the Buddhas in a reverential way: there is always humour there, just as he gleefully uses them in performance. And what about the television, that absurd box that sits in every home conveying 29 image-frames per second (25 in PAL)? With these small, witty pieces Paik invites us to use the television, the “idiot box,” as a tool for seeing.

Another spiritual work is also the earliest, Zen for TV (Tate). This was a chance occurrence that happened to a TV monitor Paik intended to use. When it malfunctioned, Paik declared it to be an artwork, an artwork resulting from both chance and the intrinsic and peculiar nature of the TV-object itself.

Paik’s works are fun, innovative and fascinating, but many of them are also beautiful. To take one example, the massive installation TV Garden (Tate), presents a veritable jungle of real plants growing wildly around a field of television monitors, all of which transmit a super-saturated video collage. The effect is hypnotic, gorgeous, sensual.

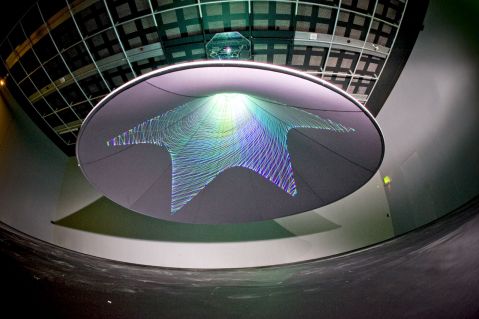

One of Paik’s last works, and his most monumental, must be the astonishing Laser Cone at FACT. It is fully immersive: a large fabric cone suspended in a dark room; you crawl into it and lie down staring up at it. How if affects you depends on how long you give it. In the first few minutes you think “ah I’ve seen laser shows before;” but stay with it. Give yourself more and more time, and the effect of the cone subtly pulls you in, as if through a funnel backwards. It is one of the most intensely meditative and synaesthetic experiences I have ever had through art. You become aware of the subtle changes in the laser formations. Despite the silence, I was watching music.

I’d like to say more about Paik but there isn’t space. I’d like to write about his fascinating and under-appreciated collaborator Charlotte Moorman ( a compelling performer), but the excellent Tate catalogue essay does a better job than I could. (If you do not get to the show, at least get the catalogue.)

It’s important to say that I experienced this magnificent show in early February, while all the while I was gripped by the events in Egypt. I was torn between my Twitter and Facebook feeds, and the art. And I could not help but reflect that this is exactly what Paik would have wanted. How he was excited by all possibilities of communication, between all kinds of people.

Paik’s ebullient and confident plunge into the then-new and mysterious, unexplored world of electronic art, making art history in the process, is totally inspiring. And, since I am aware that many, if not most, of the readers of this review are artists, perhaps that is the most important part.